*Based on a meta-analysis of 15 prospective cohort trials, including individuals aged 7-18 years in which BMI values were recorded from childhood into adolescence or adulthood.

Adolescent obesity

There is an adolescent obesity epidemic in the United States, and its causes are multifactorial3

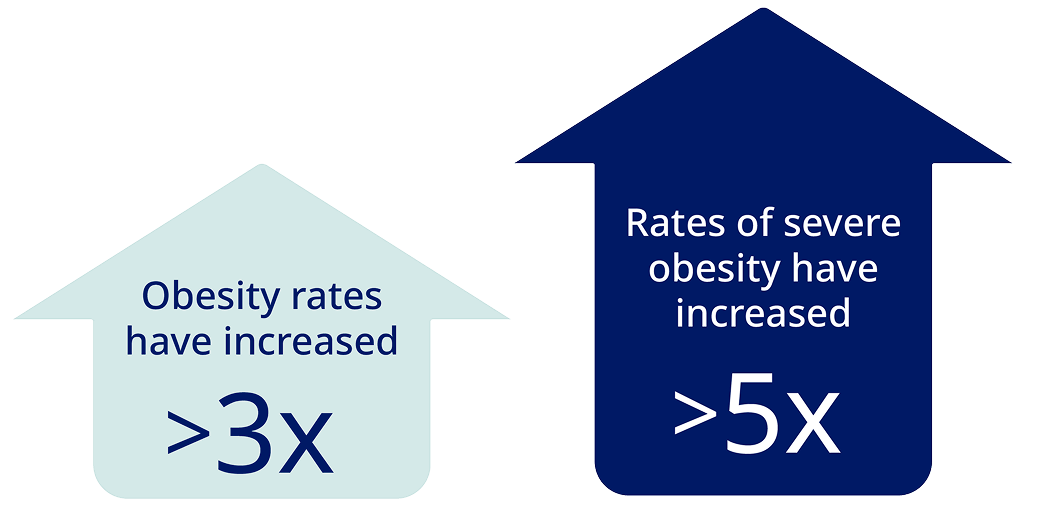

The obesity prevalence among adolescents aged 12-19 years in the United States is 22.2%.4 Since the 1970s5†:

†Data of individuals aged 2-19 years from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2017-2018.5

“When I’m working with an adolescent, I explain that family and genetics are things we can’t change, but they don’t have to have the same fate as their parents. We can make a plan together to change the cycle.”3

Holly Lofton, MD

Clinical Associate Professor of Surgery and Medicine

Director, Medical Weight Management Program

There are many facets to adolescent obesity

Explore the sections below to learn more.

These include:

- Dyslipidemia

- Prediabetes

- Type 2 diabetes (T2D)

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

- Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)

- Hypertension

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

Factors that are associated with increased prevalence of obesity among adolescents include3,7:

- Having parents with obesity

- Certain ethnic and racial backgrounds—eg, Hispanic or non-Hispanic Black

- Lower-income households

- Lower head-of-household education level

Obesity rates may be affected by the types of food adolescents eat. Fast-food consumption, lack of access to fresh food, and sugar-sweetened beverages have been associated with obesity in children.3

Adolescents with obesity may experience weight stigma, teasing, and bullying, which may lead to feeling social isolation, reducing physical activity, and avoiding seeking help for their weight.3

It starts by acknowledging their experiences and setting up long-term strategies. Also consider ongoing monitoring, health-behavior coaching, lifestyle-modification plans, and pharmacotherapy when indicated.3

For those patients aged 13 years and older with severe obesity, bariatric surgery evaluation should also be considered.

‡Based on a meta-analysis of 15 prospective cohort trials, including individuals aged 7-18 years in which BMI values were recorded from childhood into adolescence or adulthood.1

In a global study of 5,275 adolescents with obesity who completed an online survey about their weight8§:

34% of adolescents obtained their information about weight management from YouTube.8

28% of adolescents obtained their information about weight management from other social media.8

24% of adolescents obtained their information about weight management from their HCPs.8

§Based on data from a cross-sectional, survey-based global study aimed to identify perceptions, attitudes, behaviors, and barriers to effective obesity care among adolescents with obesity (n=5,275), their caregivers (n=5,389), and their HCPs (n=2,323). Participants were residents of the following 10 countries: Australia, Colombia, Italy, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Spain, Taiwan, Turkey, and the United Kingdom.8

The subject of weight and body image can be sensitive for adolescents.3 An important first step for health care professionals like you is to help caregivers understand and accept that their child has obesity and recognize the potential implications.9 In fact, when caregivers talk to children about weight, it is important to emphasize healthful eating.7

In a global survey of 5,389 caregivers of adolescents with obesity, 34% believed their child’s weight to be normal or below normal.8|| Educating them about how increased BMI in younger patients relates to obesity in adulthood might help caregivers understand the potential risks of adolescent obesity.2

Acknowledge how complex obesity is. Utilize people-first language, such as saying “adolescents with obesity” instead of “obese adolescents.”3

||Based on data from a cross-sectional, survey-based global study aimed to identify perceptions, attitudes, behaviors, and barriers to effective obesity care among adolescents with obesity (n=5,275), their caregivers (n=5,389), and their HCPs (n=2,323). Participants were residents of the following 10 countries: Australia, Colombia, Italy, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Spain, Taiwan, Turkey, and the United Kingdom.8

BMI, body mass index; HCP, health care professional.

diagnosing

AAP Guidelines for Adolescents With Obesity

Check out the full guidelines for details on how to treat

AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics.

1. Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17(2):95-107.

2. Woo JG, Zhang N, Fenchel M, et al. Prediction of adult class II/III obesity from childhood BMI: the i3C consortium. Int J Obes (Lond). 2020;44(5):1164-1172.

3. Hampl SE, Hassink SG, Skinner AC, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and treatment of children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics. 2023;151(2):e2022060640.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood obesity facts. Published April 2, 2024. Accessed June 11, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood-obesity-facts/childhood-obesity-facts.html

5. Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Afful J; Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and severe obesity among children and adolescents aged 2-19 years: United States, 1963-1965 through 2017-2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Updated February 8, 2021. Accessed June 11, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity-child-17-18/obesity-child.htm

6. Ibáñez L, de Zegher F. Adolescent PCOS: a postpubertal central obesity syndrome. Trends Mol Med. 2023;29(5):354-363.

7. Ruiz LD, Zuelch ML, Dimitratos SM, Scherr RE. Adolescent obesity: diet quality, psychosocial health, and cardiometabolic risk factor. Nutrients. 2019;12(1):43.

8. Halford JCG, Bereket A, Bin-Abbas B, et al. Misalignment among adolescents living with obesity, caregivers, and healthcare professionals: ACTION Teens global survey study. Pediatr Obes. 2022;17(11):e12957.

9. Kaufman TK, Lynch BA, Wilkinson JM. Childhood obesity: an evidence-based approach to family-centered advice and support. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720926279.